How to do - The Sun Salutation (Sūrya Namaskāra): The Anatomy Part 1 - Updated inc Videos

Update - 6 Dec 2024

The following anatomical breakdown of the Sun Salutation is detailed and divided into three parts. If you’re someone who simply loves flowing through their Sun Salutations without much thought for the specifics, this blog and analysis might not be your cup of tea. However, for those curious about anatomy and anatomical movement, this is for you.

Not every yoga teacher needs to know the details of anatomy. There are plenty of incredible teachers out there (many at my studio)—many far better than me—who couldn’t care less whether the vastus medialis is a muscle in the leg or the son of Zeus. And that’s perfectly fine. If you’re happy with your current teaching style, there’s no need to feel pressured to dive into anatomy.

That said, learning anatomy can offer a more holistic understanding of the body, enabling you to support a wider range of people beyond what might be considered the "general population." It also provides a fascinating insight into the intricacies of the human body, often leaving us in awe of how truly remarkable it is.

I also like to think of yoga anatomy—or as I prefer to call it, functional anatomy—as an entry point for those who might eventually pursue deeper studies, such as training to become a physiotherapist. If that’s your goal, or if you simply want to better understand your body and movements, this blog (and its accompanying posts) will be a helpful resource.

Remember, anatomy isn’t for everyone, and that’s okay. Some teachers use their basic understanding of anatomy to sound sophisticated in class, while others, like me, use it as a way to connect more deeply with their own bodies. Whatever your reason, know that studying anatomy takes time. If you’re ready to dive in, I hope you enjoy the blog. If not, feel free to skip the anatomy parts and just explore the techniques I share.

Either way, smile and enjoy the journey! 😊

To provide context - in the Videos below, Yoga Teacher Emma Talbot shows the breath count for Sun Salutation A & B and then Zahir instructs Emma through the classic sub-continent version of the San Salutation.

Understanding Sun Salutations: Anatomy, Origins, and Variations (originally published 11/09/2017)

This blog is primarily for our Teacher Trainees but can also be helpful for any regular practitioner or anyone interested in understanding the anatomy of yoga. When it comes to anatomy and asana practice, things can sometimes get a bit complex. You don’t need to know the difference between your sartorius and your sternocleidomastoid to enjoy your yoga practice.

But for teachers, having a basic understanding of anatomy gives us the tools to guide our students safely. For example, knowing the knee is a hinge joint helps us keep the front knee safe in Warrior 2 by cueing the student to avoid letting it collapse inward (which has the potential for injury but is not necessarily dangerous - an important distinction).

In this blog, I’ll break down the classical Sun Salutation (Surya Namaskar) sequence, giving you insight into what muscles are working and stretching at each step.

The Origins of Sun Salutations

Mythologically, Sun Salutations are connected to Hanuman, the monkey god and beloved devotee of the sun. The idea of offering gratitude and praise to the sun through movement has ancient roots. However, in modern yoga, Sun Salutations were popularized by the legendary teacher Krishnamacharya in the early 20th century. He integrated physical postures with breathwork, making Surya Namaskar a foundational part of modern yoga practice.

Today, there are several variations of Sun Salutations depending on the style of yoga you practice, but the principles of breath synchronization and honoring the sun remain at the core.

The video below shows me performing the regular Hatha Yoga Sun Salutation (as taught by me in the earlier video to Emma). Call it classic, if you will. This version, which I will refer to as the "classic version" for the remainder of the blog, involves a lunge back on each side. In the first round, you step back with the right leg, and in the second round, you step back with the left leg. Once both sides are done, this completes one round of a classic Sun Salutation.

This video below is of my amazing wife Laura Akram - https://www.instagram.com/_laurayoga/

Here, Laura demonstrates the Ashtanga style Sun Salutation A (as instructed with the breath count in the earlier video by Emma). Most Vinyasa-based classes or styles also incorporate this version. So, when I mention the Ashtanga or Vinyasa style, this is the version I am referring to — the one with the jumps and Chaturanga.

Let's Get To a Simple Breakdown of Sun Salutation

1) TADASANA - MOUNTAIN POSE

The first part of both the classical and Ashtanga versions of the Sun Salutation sequence is Tadasana, also known as Namaskar-Asana or Pranam-Asana. While the names may vary, they all refer to the same foundational standing posture, which symbolizes grounding and stillness, much like a mountain.

Different schools of yoga offer varied approaches to this standing posture. For instance, some traditions suggest standing with the feet close together, while others encourage keeping them hip-width apart or with heels touching. Similarly, some schools prefer the arms by the sides of the body, while others, like in my practice, advocate for bringing the hands together in a prayer position (namaskar), with the thumbs lightly resting against the chest.

There is no single "correct" way to perform Tadasana; the variations reflect different schools of thought and teaching. Ultimately, the essence of the posture remains the same: it is about creating balance, awareness, and a solid foundation from which to begin the practice. Whether your feet are together or apart, or your hands are at your sides or in namaskar, what matters most is cultivating presence and alignment in the body.

In this Mountain pose the mind helps the body find balance and poise. The early focus should be on finding an even balance between the left and right side of your body. B.K.S Iyengar would often say that most people do not have balance in a basic standing posture. He would say that many ailments existed as a result of not being able to stand on both feet correctly.

Start by bringing the feet together. Toes touching each other or toes apart is really a personal preference. Re-visit my earlier blog on this subject. Press the heels evenly into the ground. This activates the calf muscles statically which helps keep your knees stable. The thighs (quadriceps) are then evenly contracted paying special attention to the vastus medialis quadricep muscles that sits to the inside of the leg. You don't need another 'lecture' on this muscle so here is a quick reminder.

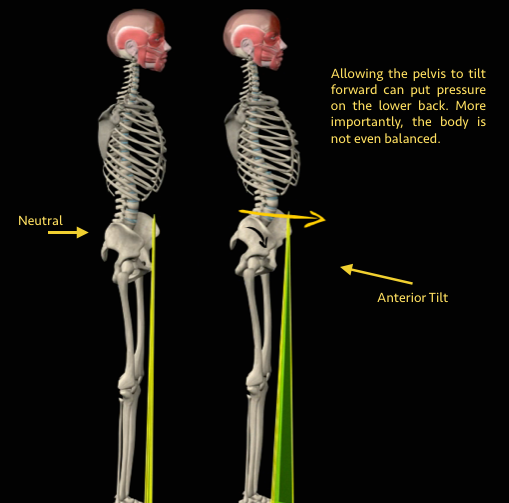

Working our way up to the hips, what you are looking for is a neutral pelvis. What is a neutral pelvis? This is when your pelvis is sitting in a natural position where it is not being pulled forward (by muscles or gravity) or backwards. Gently squeezing the muscles of the backside (gluteals) and pulling the navel in towards the spine (transverse abdominis) generally help find this natural position. B.K.S Iyengar would cue this action by telling all his students to "tighten the buttocks". You can take your hands to your hips and move the pelvis backwards and forwards until a position is found that feels neutral to you.

BELOW - A video on Neutral Pelvis (excerpted from our online Anatomy CPD course)

Next the chest is lifted by gently contracted the trapezius and rhomboid muscles. The shoulders are relaxed and drop away from the ears (potentially stretching the upper trapezius muscle). Or, in simpler language, lift the chest without exaggerating the posture. You want awareness of posture but many students can overdo it and turn this into a slight backbend.

The hands are then brought together in Namaskar. Thumbs to the chest and elbows relaxed. The eyes are then closed so the focus can now start on your breathing. On an inhale your chest should lift, ribs expand outwards and it feels like your belly starts to fill up. This is your primary breathing muscle the diaphragm which is contracting

As you hold your breath there should be awareness of your standing posture. You are still upright with your spine elongated. As you exhale (this feels like the belly starts to empty), further relax your shoulders but maintain an upright posture. Your upper shoulders and neck should essentially feel light. Personally, I also "check-in" with my jaw and try to relax these muscles. If my jaw feels locked and tight, my neck also tightens (for anyone interested, some of the jaw muscles include the masseter and the temporalis) .

Before you exit your mountain pose, your body is balanced. The left and right sides are in equilibrium, the spine is long and the breathing is slow and controlled. Tadasana is the foundation pose for all other asanas. Those who practise with me will understand the under appreciated benefits of this pose. Most people are simply NOT ready to adopt the next pose in a yoga class. This often leads to poor technique and confusion within the student. Adopting tadasana can help the student re-align and re-set their bodies. Both the body and the mind can find strength, stillness and steadiness.

If you're thinking there's a lot to consider, you're absolutely right. There is. But everything starts from this foundation. From your feet creating symmetry to your breathing creating an internal calmness, all of this helps your body stretch much more optimally. Some days, I can spend up to 5 minutes in Mountain Pose just to get my body and mind in the right place before moving into the Sun Salutation. The longer the day, the more stress endured—perhaps the more time is needed in Mountain Pose to ensure your body (and mind) is ready.

For example, when I teach this in an 8 PM class, we hold Mountain Pose longer because I feel people need more time to find their feet, stretch their feet (after being confined in shoes all day), and feel grounded. It takes longer to feel balanced, and it can feel like ages to shift the breath from chest-dominated breathing to belly breathing (using the diaphragm). Diaphragmatic breathing not only helps the body relax, but it also activates the parasympathetic nervous system, promoting calm and reducing stress. If your breathing isn’t slow, soft, and relaxed, your body senses stress, and the muscles may resist the positions you're trying to create.

This connection between breath and movement is crucial. Breathe slower and more relaxed, and your body will respond in kind, releasing tension and allowing you to move deeper into the postures. Breathe quickly, sharply, and erratically, and your body will mirror that tension, making the practice feel more strained and difficult. Remember, the breath sets the pace for your practice.

Mountain Recommendation: When you feel rushed or tense, take extra time in Mountain Pose. Let your body settle, and focus on slow, slow and soft belly breaths to create a sense of calm. By doing this, not only will your mind feel more centered, but your muscles will be more receptive to stretching and movement.

Mountain Summary: Take your time. Breathe slowly (in and out of your nose). Allow the body and mind to sync before moving forward.

BELOW - A Video on the importance of Mountain Pose

RESTRICTION - STRESS

2) TADASANA 2 - MOUNTAIN POSE

In the 2nd stage, the lower body remains the same. The palms staying together (or apart depending on the school of yoga), the arms are lifted overhead. At the same time the head tilts back. The gaze is on the thumbs (or personally, I close my eyes to make my brain and feet work closer together).

The heels continue to press into the ground. The firmness in the thighs and backside remains building the foundation for the pose.

I Inhale as I raise my arms (inhaling through the nose on a 4 count) - as I hold my breath, I lift my breast bone as high as I can almost like someone is prodding me between my shoulder blades.

MAIN STRETCH - Latissimus Dorsi, the huge fan-like muscles of the back.

RESTRICTION - Tight shoulders and the Lats

Tightness in the lats can make it difficult to lift the arms to 180 degrees overhead. Tight 'lats' will either prevent you from lifting your arms over your head or tilt your pelvis anteriorly (forward) or even both. If this is difficult then you must persevere. 180 degrees is what the shoulder joint is capable of in that position so make this your goal. To prevent the pelvis from tilting and feeling uncomfortable in the lower back, squeeze the glute muscles to resist the pelvic tilt.

3) UTTANASANA - FORWARD FOLD POSE

The fingertips reaching for the ceiling will now reach for the ground. The option here is to bend the knees to reach the ground avoiding a slumped posture, or keep the legs straight with the fingers hovering off the ground. Both options have their various pros and cons. For me personally, based on my anecdotal teaching experience, most students move better bending their knees and striking their backsides out.

Bending the knees will allow you to touch the ground taking potential pressure off your lower back. So anyone with a history of back pain may well find it preferential to bend the knees. Anyone with a torn hamstring in the past will find it more comfortable keeping the legs straight but this can lead to a slumped posture. I would recommend speaking to a teacher to work out what option is best for you right now. Eventually, in the complete pose, the finger tips (or palms) are down to the ground either side of the feet and the legs are straight.

The muscles stretched in theory start from the achilles heel and go all the way to the muscles that attach to your skull. The entire rear side of the body. I say in theory as not everyone will feel a stretch in these parts. If your body is flexible enough, the pose is pretty relaxing. From your achilles, this pose stretches the calf muscles, then your hamstrings, followed by the muscles into your backside. The stretch can also be felt into your lower back, the muscles that run all the way up your spine (erector spinae) and your lat muscles. The muscles shown in yellow in the image below are being stretched.

Back to Breathing – If you inhale and reach up (on a 4 count), hold your breath for a 2 count as you lift your breastbone, then exhale on a 6 count as you reach for the ground.

The most common mistake I’ve seen in my many years in the game is that people do a quick, sharp exhale and then bend forward. To me, this indicates a stressed breath, perhaps from not bringing in enough oxygen in the first place. Try to inhale for a 6 count. And as much as you can, try to inhale and exhale through the nose. The mouth stays closed without gritting the teeth.

RESTRICTION - For most students, the primary restriction is the hamstrings. However, it’s important to remember that every body is different. Injuries, sports, daily habits—all of these factors contribute to restrictions in yoga poses, which makes the concept of restriction completely theoretical. What feels tight for one person may not be an issue for another, and that's okay.

When the hamstrings are tight, they pull the pelvis backward, causing the spine to round during the forward fold. This can create discomfort or even strain in the lower back. The simple remedy? Bend the knees slightly to ease the tension in the hamstrings. Not only does this relax the hamstrings, but it also allows for better spinal alignment, making the fold safer and more effective.

Bending the knees isn’t just a “modification” for those who aren’t flexible enough—it's a smart adjustment that honors the natural differences in our bodies. The goal isn’t to force the perfect forward fold; it’s to find a version of the pose that feels right for your body in that moment. By doing so, you protect your lower back and create space to breathe more deeply into the pose.

Sometimes, there’s a tendency to push through tightness in order to achieve what we think is the “ideal” shape. But the real yoga happens when we listen to our bodies and respect our current limitations. By bending the knees, you're not compromising the pose—you’re creating a safer, more mindful practice. Over time, this approach builds a healthier relationship with your body and your yoga practice.

Please read my blog on Paravti & Shiva to better understand this.

Note:

In the Ashtanga tradition or a typical modern Vinyasa class, it’s common to move from a forward bend into a "halfway lift" and then jump straight back, either into a plank (top of a press-up) or directly into Chaturanga (refer back to the video above of Laura doing this). This dynamic, fluid transition is characteristic of faster-paced styles. However, if you're not quite ready for jumping back or if your practice leans more towards alignment and control, it’s important to recognize that there are alternatives.

In more classical, non-jumpy traditions (or slower-paced Hatha practices), a forward bend is usually followed by Pose 3: the backward lunge. This lunge allows for more stability and prepares the body with a bit more mindfulness before lowering into Chaturanga. If you're not used to incorporating the lunge or if it’s not part of your regular practice, feel free to skip it and transition directly into Chaturanga.

Thoughts & Recommendations:

While jumping back can look elegant and feel energizing, it’s essential to listen to your body. Jumping straight into Chaturanga, especially without proper core engagement, can sometimes compromise the shoulders or strain the lower back. If you’re still working on building strength or want to move with more control, stepping back into a lunge offers an excellent alternative. It allows you to create more space and move with intention, ensuring each part of your body is aligned and prepared for the next posture.

Always remember that the transitions between poses are just as important as the poses themselves. Whether you're jumping or stepping back, it's crucial to maintain proper alignment and move in a way that supports your body's needs, not just the flow of the class.

3) ASHWA SANCHALANASNA - EQUESTRIAN POSE (low lunge)

From the forward fold, a big step back is taken with the right foot. This lunge backwards is initiated by the glute muscles of the right leg (the glute when it contracts takes the hip into extension or behind). Once the toes touch down to the ground, the hips sink towards the ground. The sinking of the hip stretches the quadricep (as the knee goes into flexion) and gluteal muscles (hip goes into flexion) of the front leg.

There is already a stretch into the rectus femoris quadricep muscle of the right leg (as the hip has gone into extension and the rec fem is a hip flexor). This will increase when the chest is lifted and body bends backwards (extension). This movement also stretches heavily into the psoas (core and hip flexor muscle).

The more the body bends backwards (extension), the more the abdominals will stretch (when contracted the abdominals flex the spine). The front shoulder muscles (deltoid) will also stretch along with the pectoral muscles. The erector spinae muscles of the spine will contract to bend and stabilise the spine. The trapezius and rhomboids will also contract to draw the shoulder blades together aiding in lifting the chest.

Finally the upper trapezius contracts to tilt the head back stretching the sternocleidomastoid neck muscles.

All of the above, as mentioned earlier, is purely theoretical. If your breathing is erratic rather than slow, soft, and controlled, the muscles that should be stretching may actually contract or "put on the brakes." This happens because your body enters an alarm state, reacting to stress rather than relaxing. Essentially, your body will follow the way you breathe.

Another reason why this explanation remains theoretical is the way your body responds to gravity, and whether your muscles are active or passive in a given pose. This can be a bit confusing, so when someone asks me what they’re stretching, I always answer with the relevant muscle(s), but I emphasize that this is still a theoretical explanation. The body is highly complex and dynamic, and what you feel in a pose may be influenced by countless factors, from your unique anatomy to how you're breathing in that moment.

The key takeaway is that your breath plays a huge role in how your body responds to a stretch. A slow, relaxed breath invites the body to soften and lengthen, while erratic breathing signals the muscles to tighten and protect. So rather than getting too caught up in exactly which muscles are stretching, focus on maintaining a steady, calm breath—that's where the real magic happens.

MAIN STRETCH(S) - Hip flexors of the back leg (the front of the hip of the back leg). Glute (backside) muscle of the front leg. Front of the Shoulder, chest and abdominals. In theory anyway.

RESTRICTIONS - Tight hips will make it difficult to take a big step back. Poor posture and lack of awareness of the trapezius and rhomboids make it difficult to lift the chest and keep good posture.

In part two we will look at Chatarunga Dandasana and Ashtang Namaskar.

-----------

Zahir Akram

Interested in deepening your practice or teaching skills?

Our online training courses are now available, offering comprehensive content on anatomy, biomechanics, and yoga philosophy. These courses are designed to support students and yoga teachers in their continued development.

We also offer in-house Yoga Teacher Training here at our studio in Addlestone, Surrey, UK.

For more information on our online courses, mentoring or to book in-house training, email Zahir.

.png)

![Is Yoga a Religion? [Video]](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/c1de07_403e7c2368e54c4a8f7736bb1166951a~mv2.png/v1/fill/w_220,h_123,fp_0.50_0.50,q_95,enc_avif,quality_auto/c1de07_403e7c2368e54c4a8f7736bb1166951a~mv2.webp)

![Is Yoga a Religion? [Video]](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/c1de07_403e7c2368e54c4a8f7736bb1166951a~mv2.png/v1/fill/w_38,h_21,fp_0.50_0.50,q_95,enc_avif,quality_auto/c1de07_403e7c2368e54c4a8f7736bb1166951a~mv2.webp)