Yoga Poses - How Much Effort is Required?

In Light On Life, B.K.S Iyengar says; "The body will prove to be an obstacle unless we transcend its limitations and remove its compulsions. Hence, we have to learn how to explore beyond our known frontiers."

We know the value of asana. We know that with steadfast dedication, we can indeed "transcend our limitations and remove our compulsions." But how much dedication and effort is truly required? Can we simply turn up, roll out our mats, and hope for change? On the flip side, is it possible to try too hard with our asana?

The aim of this blog is to introduce you to two Sanskrit terms: Sukha and Dukha.

Sukha means delight, comfort, alleviation, and bliss, according to B.K.S. Iyengar (2008). Dukha (or dukham) translates to suffering, as in the Bhagavad Gita (Chapter 6, Verse 32). Dukham also refers to disturbances in our equilibrium and can be understood as "the absence of sukha."

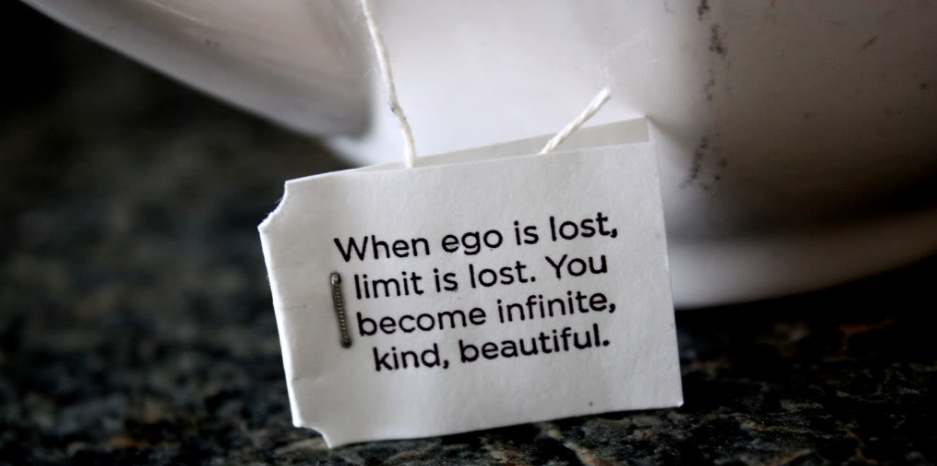

Your asana practice must be a journey between the two highways of sukha and dukha. According to yogis, this is where the ego is at its least influential. This "middle way" is where the ego exists but loses its control over you.

To find the middle way, the practitioner must first experience both the sukha and dukha of their physical practice.

The entire structure of our lives is held together by the tension of opposites, and this applies to your asana practice as well. The suffering or discomfort in your asana cannot be ignored. Krishnamacharya once said that dukha is a gift—one must learn from the suffering experienced. It is this experience of pain that helps you understand your limits.

Sukha and dukha are part and parcel of the same phenomenon. I once read that the peak of a mountain and the valley at its base are not two separate things—they are part of the same reality. The deep valley exists because of the rising mountain, and in the same way, the mountain is possible because of the valley. One cannot be without the other. You can only appreciate the magic of light due to darkness. As John Steinbeck said, "What good is the warmth of summer, without the cold of winter to give it sweetness?"

Love and war, poison and its cure (that wasn’t intended to rhyme), sadness and happiness, left and right, the body and the soul—these are all sides of the same coin. The Taoists have a way to symbolize this: the yin and yang symbol. We often see black and white, right and wrong, good and bad, but it’s actually fluid. One melts into the other, with each containing a part of the other. These things aren’t contradictory; they’re complementary. They’re two parts of a greater whole.

The great Lao Tzu says that opposites are not truly opposites, but complementaries. He advises us not to divide them, as they are interdependent. How can love exist without hate? How can life exist without death? How can heaven exist without hell? Hell is not against heaven; they are complementary and exist together. They are two aspects of the same coin. Experience both, and Lao Tzu says life will become a symphony of opposites.

In the same way that heaven cannot exist without hell, sukha does not exist without dukha. Without the experience or understanding of dukha, one deludes themselves into thinking they know sukha. But you cannot fully understand sukha without dukha. Therefore, the yogic practitioner must go through experiences that create suffering and, at times, even injuries.

Of course, I am not saying to push yourself to the point of injury. What I am saying is that if injury occurs organically, don't be disappointed. This is part of—and, in my opinion, the most important part of—your physical yoga journey. Your body will heal, and when it does, you will learn more about yourself than you could ever learn from a book (or blog). It is the experience of dukha that will help you appreciate the sweet nectar of sukha. Without this negative experience, you cannot say you have truly found sukha in your practice.

Man’s mind has always wanted to choose between the seeming opposites. He wants to preserve heaven and do away with hell. He wants to have peace and escape tension. He desires to protect good and destroy evil. In yoga, man wants to achieve sukha and avoid dukha. But one must experience one to fully exist in the other.

The philosopher Nietzsche said that a tree that longs to reach the heights of heaven must sink its roots to the bottom of the earth. A tree that is afraid to do so should abandon its longing to reach the heavens. This is a very profound statement. If you want to ascend to the skies, you will also have to descend into the abyss. Height and depth are not different things; they are two dimensions of the same reality—just like sukha and dukha.

Sadhguru Jagi Vasudev says of effort: "Logically, somebody who never put effort into anything should be the master of effortlessness. But it is not so. If you want to know effortlessness, you need to know effort. When you reach the peak of effort, you become effortless. Only a person who knows what it is to work understands rest. Paradoxically, those who are always resting know no rest; they only sink into dullness and lethargy. This is the way of life."

Once the practitioner experiences both ends of the spectrum—the suffering in the asana and then the stillness and ease of the asana—the goal from that point onwards is to find the middle way between the two. If the body is pushed into dukha too often or too regularly, both the body and mind will suffer. On the other hand, if the yogi continues to hover in sukha and only wants to experience the ease of the pose, nothing changes. There is no progress for the mind or body, and the body remains within its limitations. The middle way will eventually result in each asana you practice becoming steady and comfortable. Patanjali, in the Yoga Sutras, says of asana: "Perfection is achieved when the effort to perform it becomes effortless, and the infinite being within is reached."

From a yogic perspective, what must be understood is that it is, in fact, the ego that is behind the yogi's suffering, and it is the same ego that prevents the yogi from pushing their body toward more advanced asanas. The ego is what drives practitioners toward injury. The ego creates a competitive environment within us (which, to be fair, isn't always bad) and convinces us to keep pushing and pushing. We ignore common sense and advice, only to end up in the osteopath’s clinic.

The ego, or the mind, wants us to do more and more. The mind is born out of hope. The mind is the constant demand for more—it says, "More. Try harder. Push further. Bend a little more." Whatever you give it, the mind says it is too little and demands more. Psychologically, this drive pushes you beyond pain and into the dark realms of dukha because you feel your efforts are not being rewarded or recognized as good enough. Maybe the ego is pushing for more and more recognition?

However, pushing yourself isn’t what leads to dukha. It’s not knowing when to slow down. Dedicating the right amount of effort and time to ensure that the body does not become a barrier is important. A painful body can become an obstacle, and so can a compulsive one.

The same ego is also responsible for some of our more "restorative" approaches to asana. We avoid pushing our bodies out of fear—fear of failing and looking silly. We fear failure. The ego cannot handle the disappointment of a failed attempt at headstand, for example. To protect itself, the ego convinces us that "advanced" poses are just for show-offs. So, we take the restorative route and end up staying within the same limitations and compulsions that Iyengar warns us about in Light On Yoga.

There is no real difference between someone who pushes themselves to injury and someone who remains trapped within their limitations. One is afraid in a "positive" way, while the other is afraid in a "negative" way. The difference is only in perspective, but both are driven by fear. The yogi who keeps hurting themselves while trying to master Scorpion Pose is afraid of not achieving something they have set for themselves, or of failing a challenge. Meanwhile, the yogi who won’t attempt Scorpion Pose because they believe it's only for show-offs is afraid of failure. In both cases, the ego is in control.

The restorative yogi should not live within the confines of their insecurities. Effort is required. As Sadhguru says: "The whole effort of the spiritual process is to break the boundaries you have drawn for yourself and experience the immensity that you are. The aim is to unshackle yourself from the limited identity you have forged, as a result of your own ignorance, and live the way the Creator made you—utterly blissful and infinitely responsible."

The key is to find the middle ground between pushing yourself toward advanced asanas and knowing when to ease off. This is the delicate balance between sukha (ease) and dukha (discomfort). I came across a quote that captures this beautifully: "There’s no need to sharpen your pencils anymore. Even the dull ones can make a mark." In other words, sometimes you don’t need to keep pushing your limits. What you’re capable of right now is already remarkable. Take a moment to appreciate how far you've come rather than constantly striving for more.

Lao Tzu offers timeless wisdom when he advises us not to seek victory over life. The moment you try to conquer life, it will inevitably defeat you. He says, "Ask the Alexanders and Napoleons; if you try to be victorious, you will be defeated." His advice? “Don’t try to be victorious. Then nobody can defeat you." This subtle insight can be applied directly to our asana practice. Don’t approach your poses with a mindset of conquest. Instead, let go of striving, and you’ll find that success follows naturally. Don’t chase glory—simply be, and what you need will come in its own time.

I recently came across an interesting reflection on the conflict of the Indian ideal, drawing a parallel to Bhagavad Gītā. The story of Arjuna teaches that living passively can be detrimental. Arjuna, a kind-hearted and righteous man, didn’t want to engage in conflict. His doubts and fears almost paralyzed him, threatening to enslave not only him but everyone around him. The core message of the Gītā, however, encourages us to follow the path of Kṛiṣhṇa, who, though not a warmonger, understood his duty and role. Kṛiṣhṇa knew who he was, his purpose, and what he was worthy of. His dharma—his duty—was to become the best version of himself, and in doing so, he remained free, even in the face of war.

This has clear parallels with our asana practice. Many practitioners are overly passive with their bodies, not fully appreciating the incredible, divine potential within them. In doing so, they enslave themselves to their limitations and insecurities, and sometimes, their fears and doubts spread to others around them. Perhaps "going to war" is an appropriate metaphor—not in a violent sense, but in the sense of confronting and overcoming our own egos. By pushing ourselves within reason, we avoid becoming prisoners of complacency. Of course, this "war" isn’t about becoming reckless, like some warriors in the Mahābhārata who became consumed by their desire for victory. It’s about finding the courage to challenge yourself while maintaining balance.

Kṛiṣhṇa’s two legs can be seen as symbolic—one for peace, the other for war. A person who can’t fight for what’s important is missing something, just as a person who can’t find peace is incomplete. The ability to engage in both is crucial. Similarly, in asana practice, we must find a balance between sukha and dukha, comfort and challenge. Without both, we are missing an essential part of the practice.

So, don’t get caught up in the idea of suffering for your art or pushing yourself to extremes. Instead, aim for the middle way, where effort and ease coexist, and where a true symphony can arise within the soul.

SUMMARY -

Your asana practice, like life itself, is a delicate dance between sukha (ease) and dukha (discomfort). The key is to find that middle path—not pushing ourselves recklessly toward advanced poses, nor staying comfortably within our limitations. As Lao Tzu reminds us, striving for victory often leads to defeat. In yoga, this striving might manifest as injury or frustration. But if we approach our practice with humility and patience, without the need to conquer every pose, we will find that success arrives naturally, in its own time.

The teachings from the Vigyan Bhairav Tantra resonate strongly here. Shiva, in his dialogue with Parvati, doesn't prescribe aggressive effort but instead encourages a gentle attunement to the present moment. The tantra’s 112 techniques show that true mastery comes from balancing effort and surrender. When you stop trying to control or force outcomes, you open the door to deeper awareness and transformation. This teaching echoes the middle way —between pushing beyond our limits and staying too comfortable.

By accepting both effort and surrender, both sukha and dukha, we step into a space where true transformation can unfold, and the middle way becomes a living practice—not just in yoga, but in all aspects of life.

Zahir Akram - Eternal Seeker

---------------------------------

Interested in deepening your practice or teaching skills?

Our online training courses are now available, offering comprehensive content on anatomy, biomechanics, and yoga philosophy. These courses are designed to support students and yoga teachers in their continued development.

We also offer in-house Yoga Teacher Training here at our studio in Addlestone, Surrey, UK.

For more information on our online courses, mentoring or to book in-house training, email Zahir.

.png)

![Is Yoga a Religion? [Video]](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/c1de07_403e7c2368e54c4a8f7736bb1166951a~mv2.png/v1/fill/w_220,h_123,fp_0.50_0.50,q_95,enc_auto/c1de07_403e7c2368e54c4a8f7736bb1166951a~mv2.webp)

![Is Yoga a Religion? [Video]](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/c1de07_403e7c2368e54c4a8f7736bb1166951a~mv2.png/v1/fill/w_38,h_21,fp_0.50_0.50,q_95,enc_auto/c1de07_403e7c2368e54c4a8f7736bb1166951a~mv2.webp)